Cape Wrath Trail : Bearing towards NW !

It hasn’t stopped raining for the last three days!

Everything- rocks, vegetation, even the air that we breathe – is damp and wet!

Considerable amounts of water are flowing from every possible rise of the ground and our feet sink to our ankles on every step at the very least!

Here, in the endless peat bogs found along the west coast of Scotland, the landscape doesn’t offer natural protection. Strong gusts from the Atlantic keep lashing our faces with wet horizontal needles.

With numerous ‘traps’ all around and the thickening fog, we are literally watching out every single step by constantly checking with our poles whether the ground in front of us can support our weight. One foot follows the other, but I suddenly sink up to my thighs in a bog. With quite an effort but calm movements – as if I’m trapped in a moving sand – I finally manage to get up.

My pants are covered in a thick layer of spongy moss that looks like .. you name it. Argyris, a few meters away, doesn’t pay much attention and is struggling with half-closed eyes to take an accurate bearing towards NW.

We keep moving … always towards NW and a lighthouse that has been already shaped in our imagination!

————————

At the end of May 2019 I travelled to the Scottish highlands- along with my good friend Argiris- in order to experience this beautiful part of the world by walking the Cape Wrath Trail.

Cape Wrath Trail is an unofficial, unmarked and often trackless 370 km route that crosses the most remote, scenic and wild landscapes of the Scottish highlands and is regarded as the hardest long distance route in the UK.

————————

Fort William

In the town of Fort William, nestled at the foot of Ben Nevis, I arrived on a stormy night with the 18:30 hours bus from Glasgow. Argiris, who had already spent a week in the area’s mountains, welcomed me at the campsite with a hot soup and two words that summarized his experience so far:

“No joking dude, everything is wet here!”

The next morning, we loaded our backpacks with our equipment and 5 days worth of food (for the first half of the trip ) and went down to the pier. The early morning mist had already subsided when the ferry slipped into the calm waters of Loch Linnhe, transferring us away from the noises of modern life to the distant quiet shore .

From there, we began our journey on foot to one of Europe’s most sparsely populated areas, following traditional -centuries old – routes that farmers used in order to move their animals through the wild topography of the Scottish Highlands, well before the famine of 1841 and the so-called ” highland clearances ” that led the vast majority of the highlanders to foreign lands ( New World mostly ) in search of a better life!

Despite the complete lack of marking, as long as the weather was fine, our navigation was trouble-free and we were really enjoying to the fullest the lush landscapes that we were crossing.

However, from the very beginning, our feet were constantly plunging in water and thick mud, giving us a first taste of the new “normality” that would characterize the entire journey.

The soil of the NW highlands is so saturated by water that even on sunny days it is impossible to absorb it completely. This is one of Europe‘s most humid regions, with 265 rainy days per year and its volume reaching 4500mm.

On such trips, adaptability helps more than anything, but right choices can make our lives easier and our decision to use lightweight trail running shoes with good traction but no waterproof coating made our progress fast and efficient and by far more enjoyable, since in such an extremely wet environment – that only with rubbers our feet would stay dry – the heavier “waterproof” boots would get soaked quickly as well and would become even heavier.

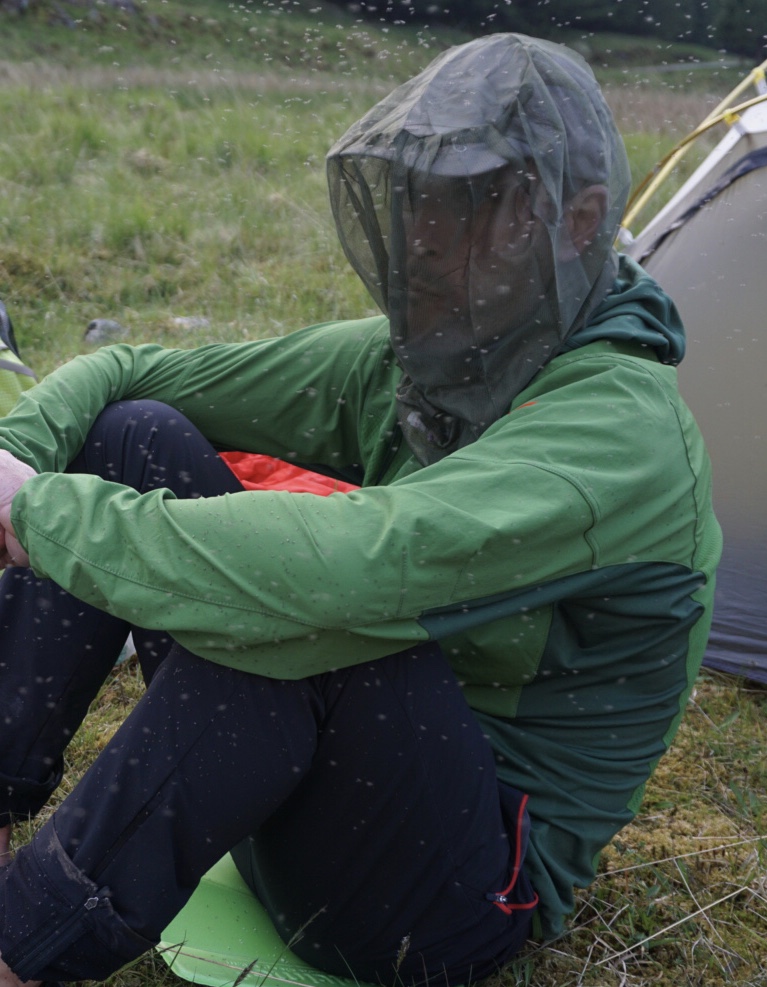

The first night, after covering 40 kilometers, we camped on the river Finnan and spent an interesting night with a swarm of highland midges, which literally tortured us until we managed to sleep.

If you haven’t experienced the feeling of being eaten alive by a swarm of Scottish midges, it’s hard to understand how annoying they can be, preventing you from doing anything (to cook, to eat, to just stand doing nothing), testing your temper quite a bit.

Barisdale Bay!

That was how we began to advance into the heart of the highlands, finding our way through mountain passes, silent narrow valleys (glens), rivers and Lochs, like the ones found in the rough Knoydart Peninsula which was systematically used as a training ground by the British commandos of World War ll.

Contouring towards Bealach Coire Mhalagain in the shadow of Forcan ridge !

And as the days were passing by, we got completely absorbed in this “routine” that we truly love ( map reading , route and camping spot selection, cooking, washing the mud out of our shoes at the end day ) and we became one with the landscape we were traveling in, like the deer that we were encountering every so often in the valleys and the eagles in the sky.

The weather was becoming more changeable day by day, as mist, light and shadows were traveling fast, giving a touch of mysticism to the surrounding landscape!

Days 4 & 5 were some of the wettest I’ve ever experienced in the mountains. Water was flowing from everywhere and every insignificant path had turned into a stream. Dense fog made route finding really challenging.

The forth day in particular we were literally soaked to the bone, fighting in the bogs for 10 hours. In the afternoon, we spotted a white structure, the Maol-bhuidhe Bothy, to where we headed without a second thought!

Bothies are abandoned farmhouses and shepherds’ huts that have been reconstructed as emergency shelters and can be used – free of charge – by those who wander during the cold and excessively wet conditions of the Scottish highlands. Most of them have a fireplace and wooden sleeping platforms.

No smoke was coming out from the chimney. We got rid of our backpacks in order to pass from the narrow door opening and entered in.

The place was dark and cold but completely protected from the rain and the wind. We were in another, dry world and that was all that mattered. A staircase, covered with a soaked and roughly spread curtain-like tent fly, led us to the attic. We soon got rid of our wet clothes, got dressed with warm and dry ones , spread out our sleeping mats, and became lethargic by watching the steam rising out from our cooking pots.

Two hours later, in the other room, we met the other three “tenants” who had given up their try to start a fire with the damp wood. They were two women from Australia and one Frenchman, all experienced hikers who were traveling together. They told us that they were impressed by the route’s character and enjoyed its silence, but found it much more difficult than they expected, mainly due to the conditions. They had already been walking for 8 days.

Bothies definitely have a charm! So, despite our clear preference to camping, we spent a total of four nights of our crossing in them, not only because of the excessive humidity but also because they form a part of the highlands travel experience.

On the sixth day, a pass led us to the famous Torridon Valley. The mountains of Torridon are considered some of the most dramatic in Britain. They have steep terraced sides and broken summit crests, riven into many pinnacles.There are numerous steep gullies running down their slopes from the peaks. Some of the world’s oldest rocks are found here!

The landscape did not resemble the previous days scenery and it was definitely one of the highlights of our trip.

We crossed the NW face of Beinn Eighe and made our way to an alpine lake, surrounded by a cirque.

We descended through extremely steep, broken and slippery ground and contoured the northern slopes of Ruadh-Stac Mor at around 400 meters to avoid the terrible blanket bogs further down.

Despite the difficulty, we moved as fast as we could and finally managed to receive the same day from the settlement of Kinlochewe, the parcel we had mailed with our food supplies for the remaining 5 days.

In the days that followed we continued crossing the highlands through equally beautiful valleys, mountain passes, rivers, lakes and bays, all named in Gaelic, a Celtic language that had been the dominant in the area during the Middle Ages and nowadays is spoken by a minor part of the population.

Sunset at Strath na Sealga valley (day 6)!

Sunset at Strath na Sealga valley (day 6)!

Golden hour at Lnockdamph bothy (day 7)!

Following river Oykel up to its source. In autumn salmons return here to spawn!

Clouds above Assynt, bringing more rain and sleet (day 8)!

And as the days and kilometers went by and we were getting closer to our final destination, the district iodine smell of the Atlantic brought by the wind was filling our nostrils.

Lunch break at Loch Gleann Dubh (day 9)!

On the 10th day we reached Sandwood Bay. A spectacular 1.5 km long beach was laying in front of us, surrounded by rocks and with a characteristic 65 meter sea stack – composed of Torridonian sandstone – guarding its southern tip.

Sandwood Bay during low tide!

We were on Scotland’s remotest beach, special amongst all those that adorn its dramatic west coastline!

Although we were just 13 kilometers away from our final destination and there were still many hours of daylight, we chose to camp at the large sand dunes, where several ships were wrecked before the construction of the 200-year-old lighthouse, beaten by the wild storms of the Northern Atlantic.

Cape Wrath

The next morning we covered the final kilometers to the Cape.

Cape Wrath took its name from the Norwegian word “hvarf”, as the Vikings used it as a navigational point during their raids on the Scottish coast.

But the English meaning of the word (rage) seems the most appropriate to describe the fierce winds and the thrashing waves that often hit the tall sea cliffs of the Cape!

When we arrived at the lighthouse, the wind was blowing hard and – guess what – it was raining!

To be honest … nothing else would fit ! 😊